How to Get Into Law School

Still Confused?

Get in touch with us for

professional guidance.

Getting into a good law school takes talent, hard work, and good grades, but it also takes learning the ins and outs of a complicated admissions system with its unique set of requirements and pitfalls. By the end of this article, you should have a handle on how to go about fulfilling those requirements without tumbling headlong into any of those pitfalls.

A Brief Overview of the Law School Admissions Process

Requirements

Law school is for people who have a bachelor’s degree of any major, and as long as you have one – or you’ll be within striking distance of having one by the time you apply – you’ve met the main general qualification for law school. The other major requirement for admission to law schools accredited by the American Bar Association (ABA) is to receive a score on a standardized exam, usually the Law School Admission Test (LSAT), but some people get into law school with a Graduate Record Exam (GRE) score instead. There are other application requirements – letters of recommendation, a personal statement, a résumé, etc. – which we will discuss in detail.

Timing

Most law schools start accepting applications in October for students who want to start law school the following August. So, for example, if you wanted to start law school in August 2025, the earliest you could apply would be October 2024. Different schools have different application cutoff dates, but the more competitive schools tend to close admissions around the end of February, while other schools often keep admissions open later, sometimes well into the summer. And law schools mostly operate on a rolling admissions model, meaning they start giving away seats at the beginning of the admissions window. In other words, if you apply in February, you’ll be competing for a smaller number of seats than if you get your application in on October 1st.

Application

Law schools usually provide an application to fill out on their websites. This can be as simple as a fillable PDF you download and return or a Google form. Plenty of them will charge you more than you might expect to apply, although many provide fee waivers for those who meet certain requirements.

Submitting Documents

Almost every law school will require you to submit through the Credential Assembly Service (CAS), an online service managed by the Law School Admission Council (LSAC), the people who make the LSAT. CAS collects all of your application materials in one place and can customize your application to different schools, for example, sending a letter from a particular recommender to one school but not another. The downside of CAS is that it’s rather expensive: $195 just to sign up and $45 to send a report to each law school you apply to. That adds up fast, although you can get full or partial fee waivers if you demonstrate the need.

The Importance of Preparation and Planning

You may have heard that law school admission is a “numbers game.” In other words, according to some pretty cynical people, LSAT and GPA are your destiny: High LSAT/GPA means you can write your ticket anywhere you want, and low LSAT/GPA spells the end of your lawyerly ambitions.

So, is getting into law school just a numbers game?

No. While LSAT scores and GPA are indeed important, they were never the whole game, and the recent trend is toward a more holistic appraisal of a candidate’s experience and circumstances. That means that you can significantly improve your chances of admission at a law school by turning in a strong package of so-called “soft factors” – your letters of recommendation, résumé, personal statement, additional essays, etc. – as well as by applying early in the cycle. To do that, it’s ideal to start planning your application months ahead of time and preparing yourself with relevant coursework and work experience months to years ahead of time.

Understanding the Admissions Process

The point of law school is to turn out successful lawyers. Using this understanding as a starting point, it’s a short jump to identify the point of law school admissions as being to find people who have the potential to be successful lawyers. What makes for a successful lawyer, you ask? Well, there are many different ways to use a law degree, so there’s no uniform answer to that question. But there are certain themes that prevail across the different areas of practice, and law schools are looking for people who fit those themes.

Factors Considered by Law Schools

A flair for advocacy. First and foremost, lawyers are advocates. Some of them advocate for their clients in the courtroom or other legal proceedings. Some of them advocate for their clients in contract negotiations. Regardless of how they do it, though, lawyers fight on others’ behalf. So, one of the things admissions officers consider is whether a candidate has a record of advocating for others and whether that candidate has a strong sense of justice.

A strong work ethic. Lawyers tend to work long hours, and law students tend to study for long hours, so another factor a law school will want to consider is work ethic and stamina. That doesn’t mean you must have worked 40 hours a week while an undergraduate, but law schools like to see applications from people who were able to balance schoolwork with extracurriculars and work and/or volunteer experience and may balk at one that looks like the candidate spends a lot of time just chilling.

A sharp intellect with a tolerance for ambiguity. The law is complex, and lawyers generally don’t get hired when the answer to someone’s legal question is easy or obvious. Instead, people hire lawyers when the legal problems are thorny, and there are arguments that can be made on both sides of an issue. And it’s not enough just to understand the law. Lawyers are legal strategists who mostly go up against other sharp legal strategists. Practicing law may not be three-dimensional chess, but plotting a course through legal conflict on behalf of a client can be a challenge, even for the quickest mind.

Comfort in the spotlight. As an advocate, it’s up to you to face a judge, jury, or reporters, or some other adversarial person on behalf of your client. While there are ways to be a lawyer that don’t involve constant scrutiny, lawyers get attention and attacks directed at them because they get paid to handle intellectual contests.

You should tailor your application elements as much as possible to demonstrate these qualities to the admissions committee.

JD vs. LLM vs. MLS

If you’re looking to go to law school because you want to be a lawyer, you’re looking to get a Juris Doctor (JD) degree. The vast majority of students at U.S. law schools are pursuing a JD. But the JD is not the only degree commonly offered at law schools.

The LLM is a Master of Law degree. (LLM actually stands for “Legum Magister,” which is Latin for “Master of Laws.” Try not to worry too much about where the second “L” came from.) This is a degree that someone who already has a JD gets in order to specialize in a particular area of law, maybe tax law or employment law, or copyright law, for instance. People who aspire to be law school professors often get an LLM in the area they plan to teach.

Then there is a more recent addition, the Master of Legal Studies (MLS). Caution: You cannot become a licensed attorney or practice law with an MLS. It may seem weird that some people go to law school without getting a lawyer’s degree, and these programs are somewhat controversial, given that people can get themselves into significant debt to get one. So, why would someone get an MLS? This degree is mostly for business professionals whose jobs are heavily law related. There is a field across industries known as compliance, and compliance professionals spend their days identifying the laws and regulations their company needs to comply with in order to stay on the right side of the law and make sure the company complies with them. An MLS is a graduate program for these professionals.

To sum up, if you’re here to find out how to become a lawyer, you’ll be applying to JD programs. Forget LLM and MLS.

Importance of LSAT and GPA in the Application Process

LSAT scores and GPA are not everything when it comes to applying to law school, but they are very important for a couple of reasons.

First, and perhaps most obviously, your LSAT score and GPA give an admissions committee a way to gauge your likelihood of success as a law student. GPA is important because it shows that you can do schoolwork and stay on track to graduate. The LSAT is important for a slightly different reason: It tests certain reasoning skills, mostly logic, and argumentation, that are central to succeeding in law school but which aren’t taught formally to most undergraduates.

While schools rely heavily on both, they tend to put more weight on a candidate’s LSAT score than their GPA. That’s because it’s far easier to compare applicants on LSAT than GPA. The LSAT is standardized. A 165 is better than a 160, full stop. But that’s not the case at all with GPA, which depends heavily on things like course load difficulty, the competitiveness of the undergraduate institution, grade inflation, etc. For example, is a 3.7 in Independent Studies from Louisiana State University better than a 3.5 in Applied Mathematics from Yale University? That’s debatable.

LSAT scores and GPA are important to law schools for another reason: rankings, most notably the US News & World Report Law School Rankings. Rankings agencies like USNWR rank schools partially on the median LSAT score and undergraduate GPA of their students. Law schools shouldn’t care about their rank, but they do because there are few better marketing tools for a law school than to be highly ranked. Schools at the top of the rankings – Yale, Harvard, Stanford, etc. – don’t have to compete for students willing to pay something close to full tuition. Luckily, there are signs that law schools are pushing back against the negative incentives the rankings place on law schools, meaning that an LSAT score or GPA that would’ve been a nonstarter ten years ago can be a starter now.

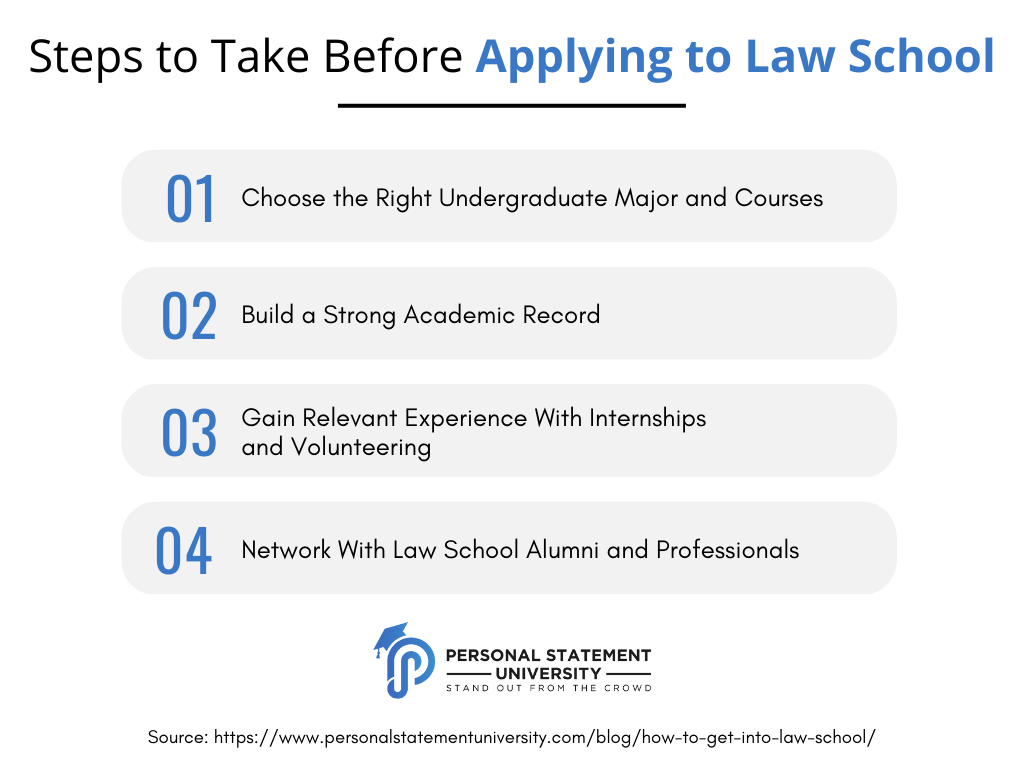

Steps to Take Before Applying

It’s an understatement to say that starting early is helpful in applying to law school. Consider, for instance, that the grades you get freshman year factor just as heavily into your GPA as those in your senior year. If you approach college with a “D-for-degree” attitude, even for a semester or two, because all you care about is graduating, you can hobble your chances at law school permanently, even if you shape up later. So, here are some steps to take before applying, and if you still have the opportunity to take these steps, do so.

1. Choose the Right Undergraduate Major and Courses

The great thing about applying to law school is that there is no “right” law school major. It’s not like med school, where if you don’t have a pre-med degree, you aren’t qualified. As long as you graduate with a bachelor’s degree of any kind, you have the right degree. So, the best way to choose a major and courses is to choose whatever you find interesting and understandable because that’s the best way to keep your grades up.

You should also take some classes that show you’re law school material. That can include taking Legal Studies courses if your university offers such classes. It also includes classes with serious writing requirements, classes where students give a lot of classroom presentations, or classes with robust classroom discussion and debate.

A last note about coursework… Most undergraduate coursework doesn’t help prepare you for the LSAT. If there’s one major that’s most relevant to the LSAT, it’s philosophy. That’s not to say you should major in philosophy just for the LSAT prep, but philosophy courses, and especially logic and critical thinking courses, will teach you some of the basics, so you might want to take one of those courses shortly before you start studying for the LSAT.

2. Build a Strong Academic Record

Law school is a professional school, like medical school or accounting school, but there’s an academic nature to the law that makes it, in some ways, more like a Ph.D. program (albeit a brief, three-year program). Most law schools have a general law review, and a lot of them also have niche legal journals for different areas of law, like intellectual property or family law. Professors, other academics, and even students write academic articles about the state of the law, often addressing a difficult legal issue and making recommendations for how that issue ought to be resolved.

There are lots of ways to get that kind of academic research and writing experience as an undergraduate. Some schools have an undergraduate legal journal or other academic journals to which undergraduates can contribute. It also makes sense to write a senior thesis or take some other kind of writing seminar where you will turn out samples that could be shared with a law school. Although most law schools won’t ask for writing samples, some will accept them, and it can help you stand out in a relevant way.

3. Gain Relevant Experience With Internships and Volunteering

Just like there’s no “right major” for law school, there is no “right experience.” It is, of course, helpful to have a legal internship with a law firm or a government agency, not least because it assures admissions officers that you have some idea of what you’re getting yourself into.

But a lot of other types of volunteer and internship experience are just as good. You go to law school to learn to be an advocate, so the more your experience has you advocating on behalf of others, the more it looks like you are comfortable with and interested in the work that lawyers do. Joining a coding club could be good for someone planning on being a patent attorney (the people who deal with tech and inventions), but for most people looking to pump up a law school résumé, it would probably be more persuasive to volunteer with a group that advocates on behalf of the homeless or children in foster care, for instance.

4. Network With Law School Alumni and Professionals

On your way to law school, there will be opportunities to meet admissions officers and law school administrators like deans or assistant deans. Representatives from law schools set up tables at graduate and law school fairs on undergraduate campuses and at regional and national law school fairs set up by LSAC or another organization. There are also increasing numbers of online conferences where you can meet law school representatives from anywhere in the world.

You should take the opportunity to attend some of these sessions, not so much because you’ll be able to schmooze your way into acceptance at your dream law school, but more because you can get a sense of the law schools you are considering. You may not get the chance to visit every school you apply to, so talking to someone from the school can help you figure out whether you’d be happy spending three years there.

Preparing for the LSAT

The LSAT is a difficult exam, and it tests skills – notably logic and argumentation – that most people start learning for the first time when they start studying for the LSAT. You’ll do yourself a favor, both in terms of your chances at admission and at scholarship money, if you get a high LSAT score, so it’s worth taking the time to do it right.

Understanding the LSAT Format and Content

There are 3 scored multiple-choice sections of the LSAT. There is also an unscored multiple choice section, called the experimental section, that you take alongside those 3 scored sections, and you won’t know which of the 4 sections is the unscored one until after the exam. There is also a writing sample that you must take on a different day, but it does not factor into your score. For your 3 scored sections, you will have one of each of the following:

Logical Reasoning (LR). Each LR question starts with a short paragraph, usually an argument. Then you’re asked a question about that argument. You might be asked what is the argument’s conclusion, or what is wrong with the argument, or how to make the argument stronger.

Reading Comprehension (RC). An RC section contains 4 passages for you to read, each about 400-500 words long. Like LR, arguments are being made here, and you’ll be tested on your ability to identify the competing arguments being made and understand the author’s position on those arguments.

Analytical Reasoning (AR). A lot of people call this section Logic Games (LG). Each AR section has 4 “games” for you to play. The way it works is that you’ll get a brief description of a fictional situation and some rules about how that situation works. It could be something like six runners running a race, and they’ll give you rules like, “Alice must finish the race at sometime before Bob,” or “Dale and Connie must finish the race consecutively,” or “Edna finishes the races either first or last.” Questions will ask things like, “If Dale finishes the race before Alice, which one of the following could be true?” Try not to be too intimidated when you start studying these games. People tend to see the most improvement in their performance in this section.

Importance of Practice and Preparation

Unless your undergraduate degree was in Philosophy, you probably will have little-to-no experience with the subject matter of the LSAT, and even that major doesn’t prepare you for the Logic Games section. The exam would be difficult enough untimed, but each section has somewhere between 22 and 28 questions to finish in 35 minutes, a breakneck pace.

There are lots of study plans out there, but people who see significant improvement from their first practice exam to test day performance usually put in at least 250 hours of studying and take the exam twice. It may not feel worth it while you’re doing it, but a great LSAT score can boost your prospects of a high-paying job by getting you into a more elite school and boosting your prospects of serious scholarship money. Give it the attention it requires.

Resources Available for LSAT Preparation

There are lots of different LSAT prep models, and they can vary widely in cost from a few bucks to thousands of dollars. It’s important to find the model that fits with your learning style and your budget.

Standalone Texts. There are books you can buy that are full-blown courses, like the Powerscore Bible series or the LSAT Trainer, both good options. There are some books that focus on just a particular section or concept, like the Loophole for LSAT Logical Reasoning, which is also a really great instructional text. If you’re just starting out, working through the material in a book is a good way to be able to get down the fundamental concepts without having to spend a whole bunch of money. You can actually get a lot of mileage out of these books if you supplement them with extra LSAT questions and video explanations available online.

On-demand Courses. The next step up the price ladder is the on-demand video course. These are often subscription-based, and if you spend months studying, it can add up. If you’re more of a lecture learner than a book learner, these courses are a good option. And they usually come with robust question-drilling functions. Its lesson videos are hit-or-miss, but 7Sage is highly recommended for being reasonably priced and having an excellent question set creator.

Live Courses. It used to be that if you wanted to learn about the LSAT, you had to get in your car and go sit in a classroom with a live instructor. There are still in-person classes out there, but the pandemic accelerated a shift already underway toward live online classes. In these classes, your instructor is live, but you’re basically doing a Zoom class. Live classes are great because you have someone to ask questions. Live online is usually a little cheaper than live in-person because the company doesn’t have to pay for a classroom. The problem with a live course is that it’s heavily instructor-dependent. If you get a great instructor, it’s probably the most effective format, but there are duds out there too.

Tutoring. LSAT tutoring is usually most helpful toward the end of a student’s studies, once the student has learned the fundamentals and needs to find areas of weakness and improve them. Tutoring can be expensive, but some tutors offer group tutoring options, which can cut the cost significantly.

Crafting a Strong Application

There are very few law schools that interview applicants as a regular step in their admissions process. It’s not surprising, given the volume of applications law schools get. The University of Virginia, for instance, got more than 7,000 applications last year for about 300 seats. And it’s not like UVA is crazy popular compared to other schools. Georgetown has gotten twice that many applications in a year before, more than once. This massive influx of people wanting to be admitted means that your application will most likely be decided entirely on what is in your application, and your application will be one of literally thousands that the school sorts through to put together an incoming class. If you don’t stand out in a positive way, it’s hard to get admitted.

Just about every ABA-accredited school will require:

1) undergraduate transcripts

2) an LSAT score (sometimes GRE is okay)

3) a personal statement

4) two letters of recommendation

5) a résumé.

Applications often ask for or sometimes require additional information, usually in the form of an essay response. Some schools will require you to write an essay called an addendum if there’s a finding of academic dishonesty or criminal conviction in your past. Many schools offer the opportunity to write additional essays to help the candidate stand out, most commonly a diversity statement, which explains how the candidate will enrich the diversity of the law school community.

Write a Compelling Personal Statement

The most important part of your application outside of the LSAT and GPA is your personal statement. It’s your chance to speak directly with admissions officers who will likely not invite you to an interview. It’s also, in a sense, your first law school exam because law school is heavily writing-based. Almost all of your grades will come from take-home writing assignments and in-class written finals. If your personal statement shows strong writing ability, that’s a plus over, and above whatever selling points you present about yourself in the body of the statement.

The best personal statements tell a coherent story that shows a trajectory through law school to the practice of law. So writing a good personal statement entails:

1) creating a career vision (although it needn’t be incredibly specific)

2) showing how you have already taken steps toward that goal

3) describing how you plan to spend three years in law school preparing yourself for that career you envision.

Gather Strong Letters of Recommendation

Unless you graduated from college five or more years ago, most law schools will require that you submit two academic letters of recommendation, meaning letters from a professor or student group advisor (a graduate teaching assistant will work in a pinch). If you’ve been out of school for five or more years, you can submit letters from colleagues, ideally direct supervisors. These letters should describe the qualities of the candidate that are important to success in law school, including things like the quality of the candidate’s classroom discussion participation, writing abilities, level of dedication, or ability to understand others’ points of view.

Describing those qualities requires that the recommender actually knows you and how you work. Do not fall into the it’s-not-what-you-know-it’s-who-you-know trap. If you submit a letter from some fancy senator that your dad knows but who doesn’t know your work, it won’t help your chances.

You should complete your personal statement before you approach your recommender so that you can share it with them as a reference. Ideally, recommendations serve as supporting evidence for the case for admission being put forward in your personal statement.

Highlight Relevant Experiences and Achievements

What experience is relevant to law school? Just about everything. If you have résumé items that are pre-law specific, whether that’s membership in student groups like pre-law society or mock trial or coursework or volunteering experience, you should, of course, focus on them in your personal statement and other essays and ask your recommenders to focus on them in their letters.

But lots of other experience is relevant. A great way to figure out how your experience is relevant is to explore the websites of the law schools you’re considering to see what kinds of programs and extracurriculars they have. Find the ones that interest you, and then try to think of what life experience you have that’s relevant to participating.

For instance, a law school could very well have lots of patent law offerings, like a patent journal and a patent litigation clinical course. If you’ve always been a tech person – maybe you built your own gaming rigs back in the day – that experience could actually be highly relevant, even though video games might not seem to have much to do with being a law student at first blush.

And any experience that shows a commitment to justice or advocacy is good. Pretty much any volunteer work or interning can be highlighted as good evidence that you are law school material.

Pay Attention to the Application Details

In addition to submitting documents through the Credential Assembly Service, each law school requires applicants to complete applications, which are mostly to be completed online. Some questions are simple yes/no or multiple choice, while others require longer responses or even attached essays. Law schools often ask for a wide range of disclosures in these applications, including criminal convictions or findings of academic dishonesty like plagiarism or cheating.

It’s important to read the application and answer the questions directly to the best of your abilities. Lawyers follow directions. It’s kind of, like, the job.

If you’re dreading the law school interview, great news! Most law schools don’t interview applicants as a matter of course. Plenty of them interview waitlisters at the end of the admissions process to fill in the gaps, but most decisions are made entirely on what’s in your application. However, interviews are not uncommon, and a good performance in an interview can put your bid for a seat over the line.

Preparing for the Interview

You should do some research on the programs and extracurricular activities at the particular school before you do the interview so you can point to them specifically when they ask you about your interest in the school. And you should have some experience to talk about prepared, ideally something above and beyond what’s in your application package. Learning something new about you will make you memorable to your interview.

You should also have questions prepared to ask them. Genuine questions about the programs (“What do students who work on the Intellectual Property Law Journal do?”) are better than generic questions about the school (“Are people nice?”) or attempts to butter up the interviewer (“What’s it like to work at the world’s most amaaaaazing law school?”).

And don’t forget to do a mock interview. Answering a question the second time is usually easier.

Common Interview Questions and How to Answer Them

In the interview, you’ll probably be asked questions like, “Why do you want to practice law?” or “Why do you think this is the right law school for you?” or “What distinguishes you from other applicants?” or “Tell me about a time you overcame a challenging situation.” Formulating a good answer to these questions requires you to know something about the school, to have some kind of vision for the future, and to be able to explain personal experience that’s relevant to that vision for the future.

Make a Good Impression

Lawyers are among the few professionals who still regularly wear suits or formal businesswear, and law students actually wear such outfits pretty regularly for things like moot court competitions and networking events. So, first and foremost, dress for the job, assuming it’s not a financial burden.

Secondly, be alert and engaged. That means keeping your phone put away and contributing more to the interview than just answering questions. Demonstrate interest in the person sitting across from you by asking questions and sharing your views.

Finally, send a thank you email as a follow-up. You can also mail a thank you note if you like a more personal touch.

Wrapping it Up

The big takeaways? Start as early as you can to develop a record of achievement that shows you’re on a trajectory to excel in law school. That means taking courses that will help you sharpen your writing and public speaking skills, participating in student groups like Phi Alpha Delta or Mock Trial, and volunteering and interning for causes that show a commitment to advocacy and a strong sense of justice. And start studying for the LSAT early. That will leave you well-prepared to craft an application package that highlights relevant skills and experience while presenting a coherent vision of law school and your legal career.

If you’d like to learn more about getting into law school or need help with any portion of your application package, don’t hesitate to reach out to us. We’ve helped lots of people get into the law school of their dreams, and we can help you too.

Let Personal Statement University Put You on the Path to the Law School of Your Dreams:

Application Consulting - Work with a 15-year veteran of law school admissions who's helped thousands of people get admitted.

Essay Editing - Whether it's a personal statement, diversity statement, addendum, or another essay, we'll make sure it's polished and targeted.

The World's Only Interactive Personal Statement Course - Learn everything you need to know to get admitted - and find the right schools for you - for just $99.